For most, the dream of being a screenwriter is never fulfilled. A quick search for tips on how to be a screenwriter will yield one consistent piece of advice, “Finish what you started writing,” a piece of advice that is tragically seldom practiced. The truth is, it’s hard to be a screenwriter, because it’s hard to milk a satisfying story out of the marrow of life. Even if a burgeoning writer manages to craft a decent script, it’s far less likely that an unknown writer will be able to attract enough attention to his script to get it produced, or even read by a meaningful party. However, there have been just enough exceptions to the heartbreaking gauntlet of Hollywood failure to give those who dream of telling their tales on the silver screen a sliver of hope.

Most people think of Sylvester Stallone as a guy that punches and/or shoots people while slurring lines out of his trademark sneer. The reality is that the Italian Stallion wrote Rocky, allegedly in one continuous sitting, and went on to win 3 of the 10 Academy Awards he was nominated for including best picture.

continuous sitting, and went on to win 3 of the 10 Academy Awards he was nominated for including best picture.

Matt Damon and Ben Affleck are two other shining exceptions to the rule. Their 1997 screenwriting debut, Good Will Hunting, remains critically beloved and managed to win the Academy Award for Best Screenplay. The popular internet rumor that the script originally called for an invasion of space aliens remains unconfirmed.

There are other notable exceptions too. When Diablo Cody wrote Juno, she had just wrapped up her career as a stripper. Blood Simple was penned by a couple of Jewish brothers, who had clawed their way up through meager production roles like assistant editor for Sam Raimi’s Evil Dead. Wes

Anderson and Owen Wilson were just some heady film dorks from Texas until a series of benefactors championed their first film, Bottle Rocket. Tarantino worked in a video store watched every movie ever made, and then wrote True Romance. Shane Black wrote Lethal Weapon, and depending on who you ask, changed the studio process forever. Aaron Sorkin wrote A Few Good Men, just as his career as a singing telegraph man was winding down. Cameron Crowe was a freelance writer for Rolling Stone before posing as a highschool student and writing both a novel, and a film adaptation about his exploits called Fast Times At Ridgemont High.

So for all the naysayers that claim that a first time screenwriter has no chance of getting published aren’t wrong, but there are exceptions. Of course, posing as a high school student, memorizing ten years worth of VHS films, and working your way through the soft core porn industry may be the price success.

Here are some great films by first-timers.

(1976) Rocky

Written, directed by, and starring Sylvester Stallone

(1997) Good Will Hunting

Written, directed by, and starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck

(2007) Juno

Written by Diablo Cody

(1996) Bottle Rocket

Written and directed by Wes Anderson and written by and starring Owen Wilson

(1984) Blood Simple

Written, directed, Produced and edited by Joel and Ethan Coen

(1982) Fast Times at Ridgemont High

Written and Directed by Cameron Crowe

(1992) A Few Good Men

Written by Aaron Sorkin

(1987) Lethal Weapon

Written by Shane Black

perfect, but it’s certainly present.

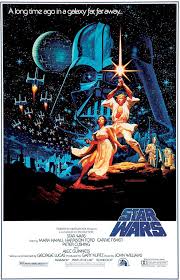

perfect, but it’s certainly present. Iron Man. All of these characters are told they have the capacity for greatness, are forced to act on that possibility, and subsequently rise to the challenge, becoming heroes and experiencing some sort of catharsis. Big Fish not only features an on-the-nose hero’s journey, it features a character actually commenting on the tropes and the reason for them as he recounts the story. Not all stories about stories are as somber as Big Fish though.

Iron Man. All of these characters are told they have the capacity for greatness, are forced to act on that possibility, and subsequently rise to the challenge, becoming heroes and experiencing some sort of catharsis. Big Fish not only features an on-the-nose hero’s journey, it features a character actually commenting on the tropes and the reason for them as he recounts the story. Not all stories about stories are as somber as Big Fish though.

delivered performances adored by fans and critics alike, he has yet to receive an Oscar Award for Best Actor.

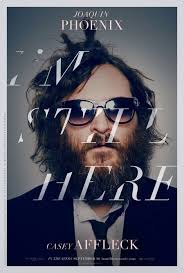

delivered performances adored by fans and critics alike, he has yet to receive an Oscar Award for Best Actor.  young minds, all too frequently resulting in alcoholism and mental illness. Often times these troubles mean the end of the performer’s career, but there are exceptions. Joaquin Phoenix is certainly no stranger to adversity. When he was still very young, he lost his brother River who was also a performer. Joaquin Phoenix has been admitted into rehab, and has publicly claimed to be narcissistic, manic, and unstable. Despite all this, his career is a brilliant example of how to turn dark circumstances into an incredible career.

young minds, all too frequently resulting in alcoholism and mental illness. Often times these troubles mean the end of the performer’s career, but there are exceptions. Joaquin Phoenix is certainly no stranger to adversity. When he was still very young, he lost his brother River who was also a performer. Joaquin Phoenix has been admitted into rehab, and has publicly claimed to be narcissistic, manic, and unstable. Despite all this, his career is a brilliant example of how to turn dark circumstances into an incredible career.

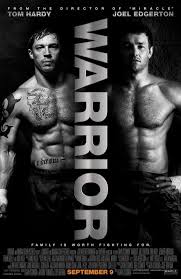

At the heart of every script is a conflict, and it is this conflict that drives the decisions of the characters. How the characters choose to reconcile this conflict is what gives the story its meaning. These conflicts manifest themselves in a variety of ways, sometimes as a single man versus seemingly overwhelming odds, or as a difficult choice a character must make that forces him to sacrifice something he loves. Sometimes this conflict manifests itself a little more directly, in the form of fists striking flesh, and feet shuffling to dodge blows, and when this happens the release of tension can be truly cathartic.

At the heart of every script is a conflict, and it is this conflict that drives the decisions of the characters. How the characters choose to reconcile this conflict is what gives the story its meaning. These conflicts manifest themselves in a variety of ways, sometimes as a single man versus seemingly overwhelming odds, or as a difficult choice a character must make that forces him to sacrifice something he loves. Sometimes this conflict manifests itself a little more directly, in the form of fists striking flesh, and feet shuffling to dodge blows, and when this happens the release of tension can be truly cathartic.

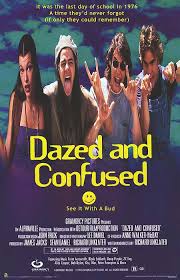

Richard Linklater’s films are a sort of challenge to the film industry. His willingness to depart from traditional techniques and narratives and to do so in such a radically independent way have established him as a perfect of example of what independent filmmaking could be. Linklater is a totally self-taught screenwriter, director and producer and has won numerous awards for his films including several Austin Film Awards. He has been nominated for the Academy Award for best adapted screenplay twice, as well as awards at Cannes film festival and Independent Spirit.

Richard Linklater’s films are a sort of challenge to the film industry. His willingness to depart from traditional techniques and narratives and to do so in such a radically independent way have established him as a perfect of example of what independent filmmaking could be. Linklater is a totally self-taught screenwriter, director and producer and has won numerous awards for his films including several Austin Film Awards. He has been nominated for the Academy Award for best adapted screenplay twice, as well as awards at Cannes film festival and Independent Spirit.